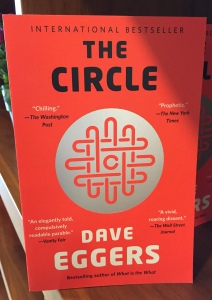

The novel The Circle lays bare the trajectory of our culture’s attitude towards online life. It illustrates both a warning and a reflection. Have we incorporated internet “liking,” posting, and commenting into our conception of “activity”? Is this what it means to be “social”? To communicate?

Imagine a fictional corporate entity resembling a magnified combination of Facebook and Google and there you have Eggers’s The Circle. The underscoring logic of the company, the founders claim, is to promote transparency and thereby a heightened sense of morality.

- If everyone could be tracked and cameras become ubiquitous (and perpetually provide live streaming) then would anyone ever dare to lie, cheat, and/or steal?

- And, given the idea that information ought to be free for all, would it be “wrong” to withhold all information including personal information?

These questions posed by the novel compel us to examine what is meant by moral action. Eggers’s work here echoes a sentiment elucidated in Camus’s The Fall (la chute). While it may be true that knowledge of being shadowed would nudge one in the direction of being on one’s best behavior, there is something left to be desired insofar as positing a definitive statement about morality. The concept of the moral agent is reduced to one who acts either for recognition or with fear of consequence.

Camus demonstrated the poverty of this line of reasoning through the character Jean-Baptiste in The Fall. Jean-Baptiste devoted a healthy portion of his day to charitable acts intentionally executed in public. He boasted of offering his seat on the bus for the elderly, for instance. One fateful day when no one was looking and he found himself confronted with a situation to help a woman in dire need he froze. His paralysis haunted him because in that moment he realized his past “good” actions could never testify to his character.

Instead, his character unfolded in the singular moment he failed to act. He fooled himself into believing that acting according to “good custom” granted him moral agent status; however, without rules and an audience the truth of his cowardice emerged.

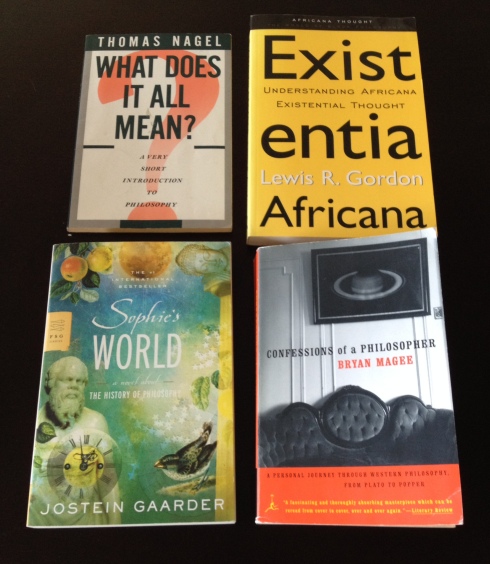

The ancient Greeks focused on character as the cornerstone to morality. Aristotle in particular argued that excellence attained by habit, practice, and the development of reason led to a fruitful and good life. To act justly and bravely, for example, necessarily includes acting with a right disposition. That is, the thrust of action must be derived from an authentic desire to be “good” and for its own sake.

Public honor, according to Aristotle, renders an inferior motive because it depends on the view of others whereas genuine “good” action is inherently self-sufficient. “Good” action originates from the agent rather than an external force.

An important distinction regarding character resides between a person who acts bravely for publicity versus a person who acts bravely for no reason other than it was the right thing to do in the circumstance. Notice the end result may appear the same, namely an act of bravery came to the fore; however, the former feels shallow since the act was a means to another end (public honor) and the latter exudes heroism.

On this point, the fictional leaders behind The Circle miss this mark. In the novel, the possibility of public praise or blame serves as the sole impetus for moral action, a Jean-Baptiste manner of thinking. Attention to the inner life of the individual, paramount for Aristotle, falls by the wayside.

On this point, the fictional leaders behind The Circle miss this mark. In the novel, the possibility of public praise or blame serves as the sole impetus for moral action, a Jean-Baptiste manner of thinking. Attention to the inner life of the individual, paramount for Aristotle, falls by the wayside.

The Circle’s constitution additionally chips away at the notion of character development by inducing a hyper attention to a life lived online which amounts to not really living at all. Hours of an employee’s day must be devoted to commenting and “liking” posts, ultimately replacing time for self-reflection and rumination. If one fails to maintain an online presence they become a pariah.

Consequently, a “self” no longer exists. The Circle absorbs all traces of it. The Circle owns it.

The concept of information sharing warps into a compunction to share one’s point of view on social media. “Information” exceeds our normal understanding of news and seeps into personal experience. When one travels, for instance, The Circle insists that pictures and descriptions be posted. To not do so violates their standard of information sharing.

Followers of the company enthusiastically chant “Privacy is theft!” Keeping an experience such as a vacation to oneself is to steal from others the opportunity to view one’s photos of a place they might be interested in visiting someday. Nothing may be kept to oneself. Moreover, to not share amounts to lying on one’s social media profile. Shouldn’t everyone know everyone’s interests and hobbies?

This “Privacy is theft!” mentality blindly embraced by the leaders and followers of The Circle resembles the mind bending claim “2 + 2 =5” from 1984. Both dystopias usher in slogans countering the readers’ sense of normalcy. But, as I stated at the beginning, Eggers’s book not only warns. It reflects. Where are the lines between private and public life blurring and how much of a role are we playing (willingly)?

The irony of posting a review about The Circle is not lost on me. Have I succumbed to the trappings of The Circle? I patiently await your comments 🙂